CHIROPRACTIC FOR PELVIC FLOOR OUTLET CONSTIPATION: WHEN YOUR GUT AND YOUR BUTT DON’T LINE UP

After 30 years of practice I am glad to report that I learn new things almost every day and for certain every week. And recently I had 2 cases, one pediatric and one adult, that made me realize that certain subtypes of constipation are closely linked to distortion patterns in the spine, pelvis, and pelvic floor.

On my wish list is the ability to take the full pelvic floor clinical management review, which may happen in the next year when I'm able to make time and travel to the teaching outfiit I have selected. In the meantime, I have been hitting the books and doing short online webinars to try to get a better understanding of the pelvic floor anatomy, which in our profession and historical training has been a little bit of "no man's zone" of management, although I've come to appreciate over the last few years that it could often be the missing link between the trunk and the lower extremity.

The tongue-in-cheek title of this blog actually comes from a patient trying to describe her problem, as she had developed some unusual constipation, which really was the inability to release stools from the very lowest part of her rectum, following a pretty severe lumbar and gluteal injury. She felt foolish describing to me the sensation that her lower rectum did not align with her anus, with the sensation that it was almost sitting too far back onto the sacrum. But in reality she was describing exactly what was happening to her. It is a known clinical presentation that has been assigned an ICD 10 code (the official medical nomenclature of every medical condition for the sake of insurance coding and research): pelvic outlet constipation,K95.02.

Constipation is a term that covers a variety of symptoms that have an equal variety of causes. Pelvic outlet constipation is a very specific form of constipation that does not involve other traditional causes (low intestinal wall muscular activity, low fiber/bulk, internal stool dehydration). It is the inability of the lower rectum to empty out the stool content through the anal sphincter. Upwards digestion and motility and bulk are okay, but things are literally mechanically stuck trying to get out at the very end. Patients will describe a different sensation from other forms of constipation, sensing that the stool is very low, causing a lot of pressure in the rectum, and an urgent need to evacuate, but no matter how much they push they feel that things are stuck and not able to get out. This can cause the patient to spend an inordinate amount of time trying to push very hard, to the point of causing local injury in the form of hemorrhoids and occasional prolapse.

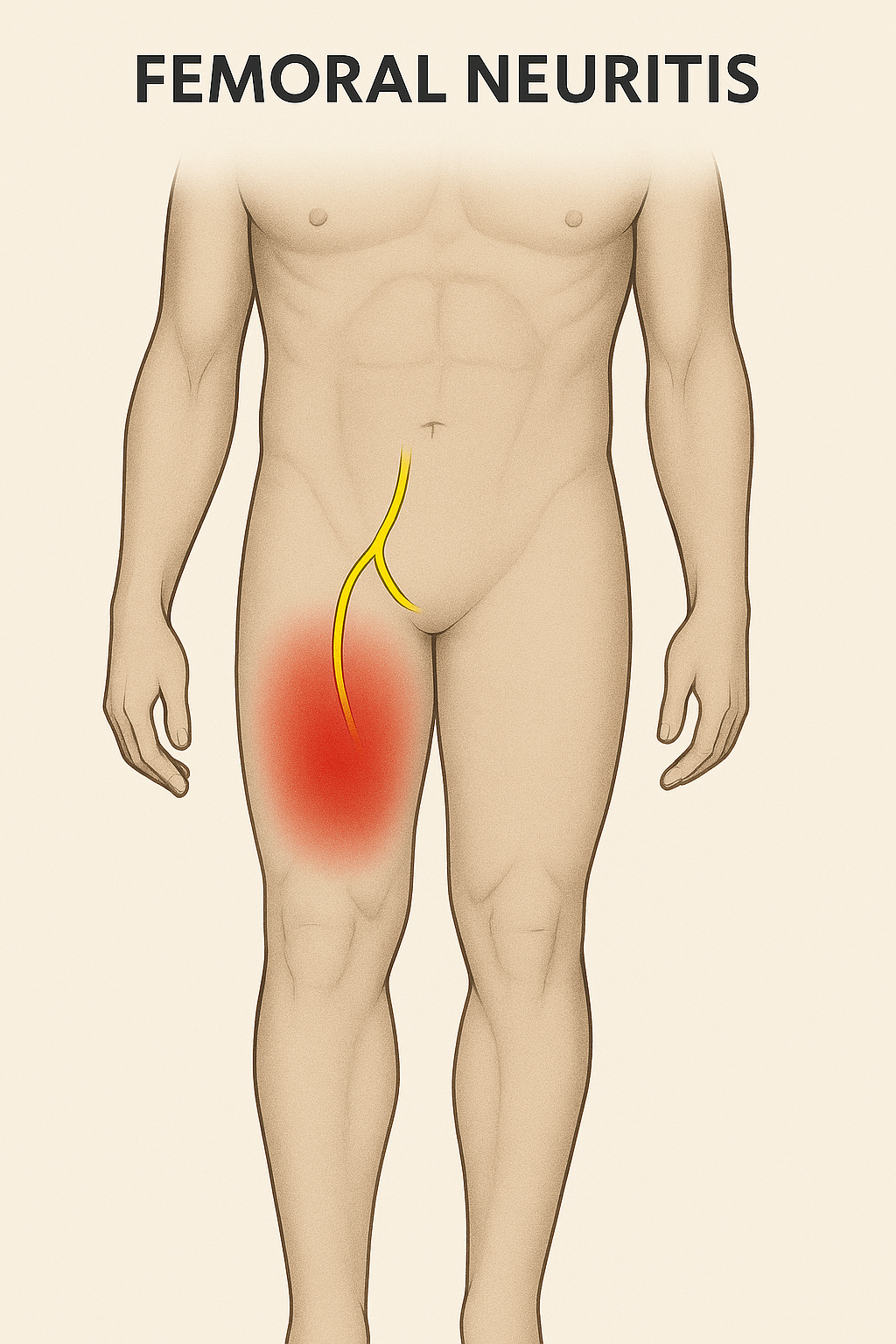

To make sense of this phenomenon you need to understand the basic anatomy of the lower colon in relationship to the pelvic floor and the pelvis itself.

The distal colon descends from the left lower abdomen into the front of the sacrum, where it's posterior to the anal opening. The muscular sphincter is surrounded by a complex set of pelvic floor muscles, which can move the sphincter further forward under voluntary control, thus holding stool in the rectum rather than letting them evacuate.

In order to let stool pass through, the pelvic floor muscles need to relax so that the sphincter can move a little further backwards and align itself with the rectum. In addition, the sphincter must be central in the pelvic floor, not shifted or pulled to one side, in order to have the easiest and smoothest stool evacuation.

If you look at the anatomical drawings of the pelvic floor muscle and the lower colon, you will notice that the pelvic floor muscles attach to the entirety of the bony pelvis, from the posterior part ( ilium and ischium, sacrotuberous ligament, tailbone) to the anterior part behind the pubic bone. In addition, all the pelvic floor muscles are innervated by by the lower lumbar segment and sacral segments.

The intimate neurological and structural connection of the pelvic floor to the lumbar spine and pelvis means that distortion patterns, trauma, repetitive strain of the lumbar spine and pelvis can result in some significant distortion of the muscular activity and tone of the pelvic floor, with the risk of chronically altering the central positioning of the sphincter in relationship to the lower rectum. This means that at the time of voluntary evacuation, it would take more effort and straining to bypass this suboptimal relationship between the lower large intestine and the outlet.

It occurred to me at the time I started writing this blog that I've probably been incidentally treating a lot of mild pelvic outlet constipation cases for a while, as a byproduct of my chiropractic treatments to the lumbar spine and pelvis. However it's only more recently that I've started paying attention more closely and in more detail to the structures of the posterior pelvic floor, which abuts structures we routinely palpate in the lower sacrum, inferior external rotators of the hip and sacral ligaments. I've also started asking the patients a few more pointed question about symptoms, which they may not volunteer, partially because these body parts are pretty private and partially because people don't make the connection between their G.I. symptoms and their lumbar pelvic symptoms.

To be effective, a chiropractic treatment in patients suffering from pelvic outlet constipation needs to incorporate several elements: addressing the structural alignment issues in the lumbar spine and especially in the pelvis; addressing the muscular imbalance of the external rotators of the hip, especially the most inferior group; addressing abnormal tone texture and scar tissue in the posterior pelvic ligaments (sacrotuberous and sacral spinous); and being able to give the patient basic information about how to do a proper pelvic floor stretch and strengthen based on which side is involved.

I'm also very fortunate to have access to several excellent pelvic floor specialty providers (physical therapist and occupational therapist) in my area of practice, who can take care of more direct pelvic floor manual therapy in patients who need it

K59.02

Outlet dysfunction constipationK59. 02 is a billable/specific ICD-10-CM code that can be used to indicate a diagnosis for reimbursement purposes. The 2024 edition of ICD-10-CM K59.

https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/K00-K95/K55-K64/K59-/K59.02#:~:text=Outlet%20dysfunction%20constipation,-2016%202017%202018&text=Billable%2FSpecific%20Code-,K59.,ICD%2D10%2DCM%20K59.